Let’s pretend for a minute that you are a new visitor to Washington DC. You look around and see a lot of streets, buildings, and other structures. You need to get from one point in the city to another. You ask me, a local, for directions. I could give you directions like this:

Go straight and then turn left at the thing. Walk along the thing through the thing. Make another left at the thing. Walk straight until you get to the thing!

Obviously, no one in their right mind would give directions like that. Let’s pretend that I can give you some more specific directions, but unfortunately, I don’t know the names of anything in this city. My directions would sound something like this:

Go straight and then turn left at the memorial. Walk along the pool through the memorial. Make another left at the monument. Walk straight until you get to the building!

That is better. Instead of “things”, we can now navigate the city by memorials, monuments, pools, and buildings. However, this still isn’t great. Like any city, there are multiple of each of these structures. You may be able to figure out where to go through some advanced logic and a really good map, but that makes life harder than it should be.

Fortunately, everything in DC has a name and we can use these names to give even more specific directions, like this:

Go straight and then turn left at the Lincoln Memorial. Walk along the Reflecting Pool through the WWII Memorial. Make another left at the Washington Monument. Walk straight until you get to the White House!

Better, right?

Navigating a website is no different

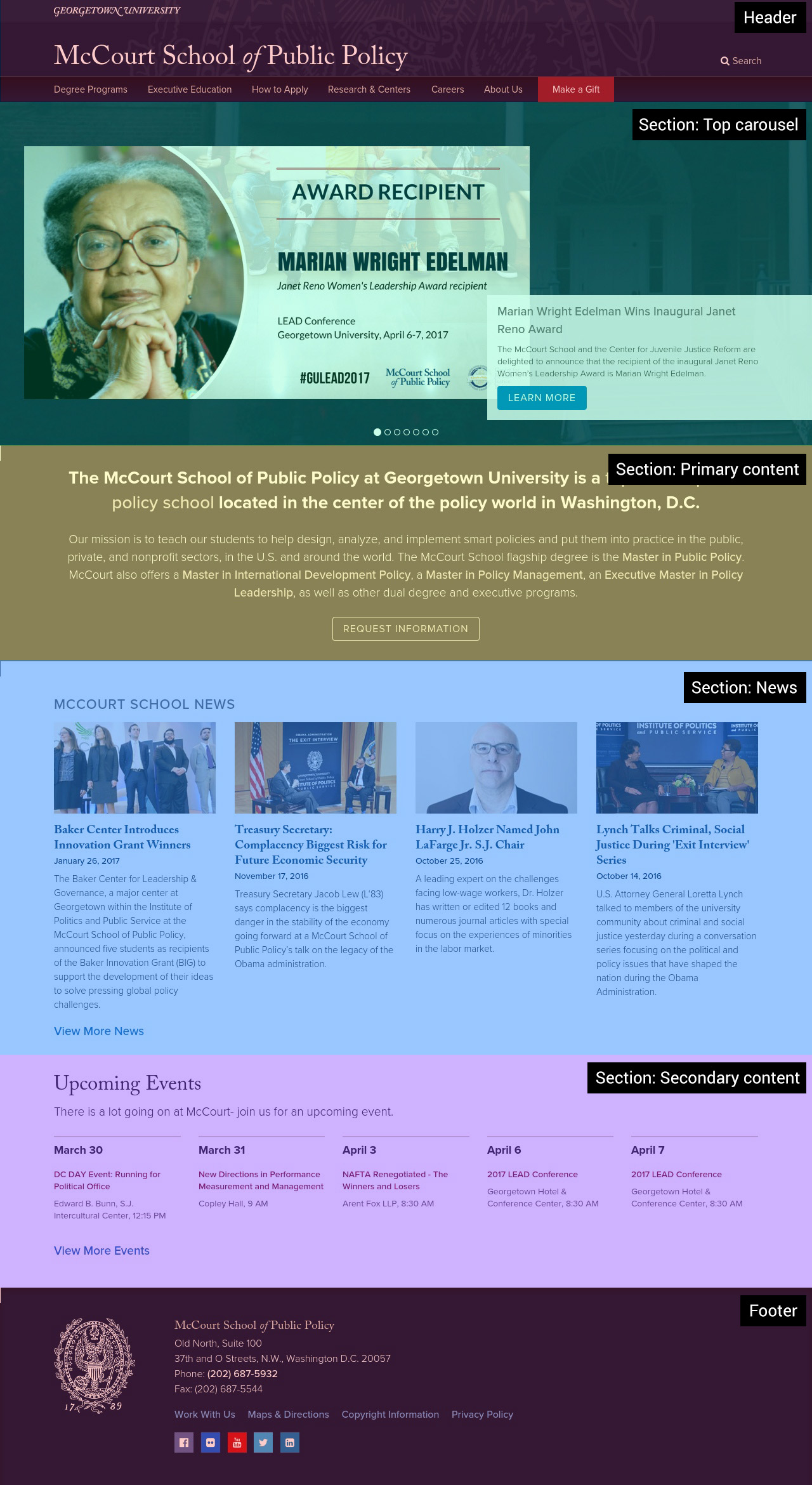

The concept behind finding your way around a website is just like finding your way around a city. Instead of buildings and monuments, you would use HTML blocks to give your users cues as to what to expect where.

As a fully-sighted user, a cue can be the site header or footer. It can be a featured video block. It can be a red emergency message box at the top of the page. It can be a sidebar containing an important note. You can make each of these blocks look distinct so that a sighted user can tell the difference between the site header and a sidebar.

A low- or no-vision user can use these same blocks to find their way around a web page. However, instead of using visual cues, like color or page placement, they use cues in the HTML code. These cues are called landmarks.

There are specific HTML tags that serve as landmarks for web users. These tags describe major features of a page. They serve the same purpose as major features of a city, such as buildings and monuments.

| HTML 5 Tag | Role |

|---|---|

| <header> | banner |

| <nav> | navigation |

| <main> | main |

| <aside> | complementary |

| <section> | region |

| <article> | article |

| <footer> | contentinfo |

| <form> | form |

Sweet! How do I use landmark tags?

The first step to using landmarks effectively is identifying the major sections of your website. Where are the site header and footer? What can be used as navigation? What major blocks of information exist on the page?

Once you have identified all of your landmarks, contain that section using the appropriate HTML landmark tag. You can nest landmarks, too. In the above example, the site navigation is inside the site header. Therefore the <nav> tag is nested inside the <header> tag.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

<header>

<h1>Landmarks and why they rock</h1>

<nav>

<a href="#">Landmarks</a>

<a href="#">Rocking</a>

</nav>

</header>

<section>

All the things about landmarks.

</section>

Landmarks and labels

A landmark is not very useful if you cannot tell them apart. Remember my first set of directions, where everything was “the thing”. Same concept here.

A landmark’s role is one way that users can tell the difference between landmarks. For example, screen readers will announce the role of a particular landmark. They will say “banner” for <header> tags and “navigation” for <nav> tags, etc.

However, what happens when there is more than one landmark of a particular role on the page? For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

<section>

<p>All of the incarnations of the Doctor.</p>

</section>

<section>

<p>All of the Doctor's companions.</p>

</section>

Users will not be able to tell the difference right away between these two sections. A screen reader will see both sections, but the only piece of information it will initially give to the user is that there are two landmarks with the role of “region”. It’s like saying that there are two buildings in my city. This can be a problem if a user is only interested in one section, but not the other.

This is where labels come in. You can give your landmarks unique labels using the aria-label attribute, so that users can distinguish one from another.

Labels are required for landmarks with redundant roles on the page. They are optional for any landmarks that are the only role of its kind. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

<header>

<h1>Doctor Who!</h1>

</header>

<section aria-label="The Doctor">

<p>All of the incarnations of the Doctor.</p>

</section>

<section aria-label="The Doctor's companions">

<p>All of the Doctor's companions.</p>

</section>

Anything else I need to know?

There are a couple of additional requirements to know about when using landmarks.

- Every piece of content on your web page is required to be inside of a landmark. Having content outside of any landmark is like having a couch in the middle of the street — it’s kind of weird and your couch really belongs in a building.

- Always use the appropriate HTML landmark tag to markup your landmarks. You could use the role attribute to assign a landmark role to another random tag — i.e. <div role=”banner”>. However, that is messy and not recommended. The HTML landmarks tags have their roles built in. Less code = better.

- Make sure your landmark labels make sense to a human. After all, they will be read by (or rather, to, via a screen reader) a human. So, don’t treat the labels like IDs.

- Make sure your landmark labels are unique. New York City does not have two Empire State buildings. Similarly, your webpage should not have two “All about the TARDIS” region landmarks.